This post is submitted by a subreddit user, JaffaKetchup (u/bad-at-exams).

I recently did a 2-month solo Interrail trip starting on the 15th of September 2025. It ended up as ~14,000 km in the end, through 21 countries. That’s the distance from the top of Canada to the bottom of South America in a straight line. It’s been a little while since I came back, but I’ve been sitting on it and just letting myself remember the best parts and the most important parts.

Feel free to follow along at this Trainlog link. If you squint a bit, it kinda looks like the UK got a tad bit drunk?

My initial aim for this trip was to reach the real most Northern point of Continental Europe and Norway (a little bit more north than Nordkapp), all without touching a car or taxi (or any other mode of private transport). Partially inspired by a well-known trainhopper, but without the use of the car at the end, and making a full trip of it.

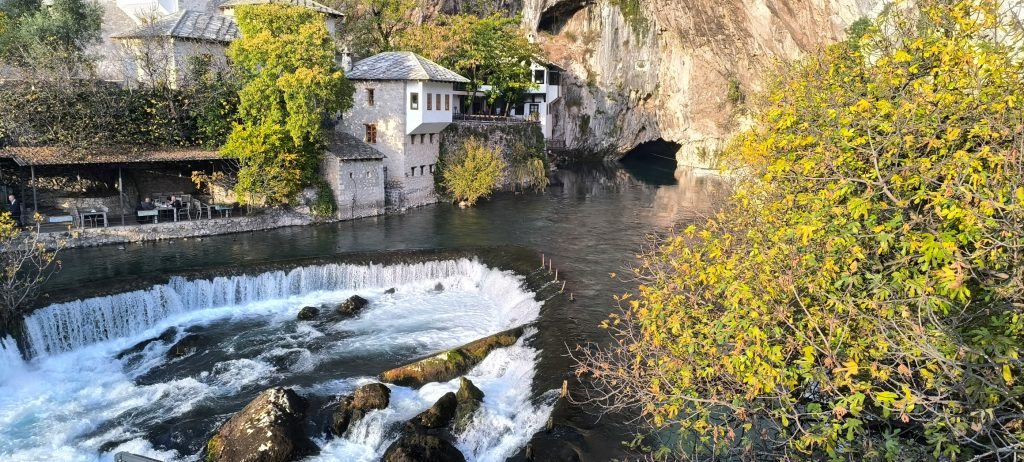

This trip report consists of 4 parts – each one representing a very different environment to the last. Part 1 is the journey to Nordkapp. Part 2 is the journey back down to Central Europe. Part 3 is the journey that was Serbia. Part 4 is the journey home via Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

It turned into quite a bit more than I initially planned. Along the way, besides riding some lesser ridden routes, I also ran into the police, took part in overthrowing a government, needed an X-ray, and had some low points. I started solo and finished solo, but I did meet people along the way. And I enjoyed it.

Hopefully this report contains something useful if you’re looking to do your first trip – I’ve sprinkled in a couple of things I learnt along the way every now and then, feel free to ignore and find out yourself, that’s how I did it. If you’re an Interrail veteran, hopefully it’s a nice read and maybe a bit of inspiration.

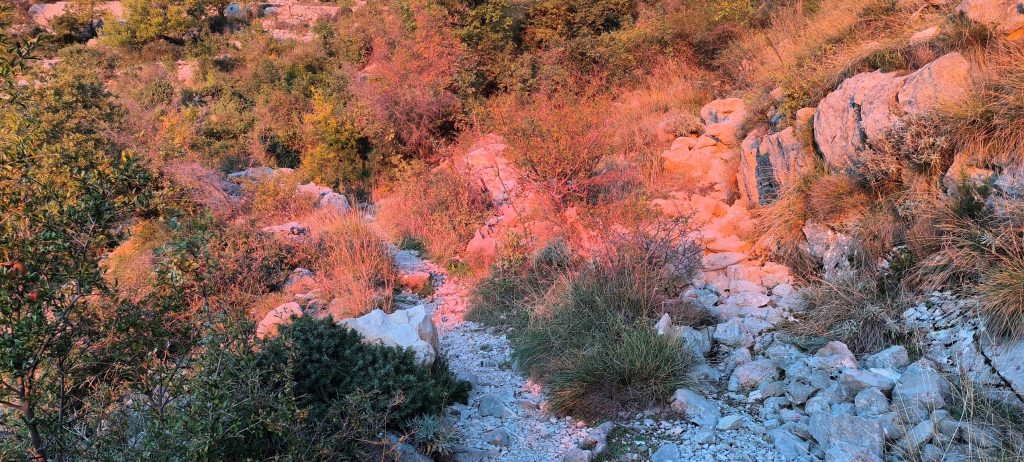

I wasn’t travelling particularly to party, or to do particularly anything other than be there. I was interested in socialising, to try and escape my natural introversion, but it happened sometimes and sometimes it didn’t, as is normal for a solo trip, especially of this nature and this time of year. It also turned into a bit of a sunset-hunting trip, so if you like sunset photos, hopefully there’s at least one good one.

I got absolutely spoilt with the weather – I couldn’t really have asked for any better. I also got spoilt with the timing and a fair amount of luck, although of course, it all balances out and there were some moments which weren’t so lucky (but still memorable), and a couple I’d rather not think about. But that’s what makes a trip a trip – the good, the less good and the not-so-good.

All in all, I’m not sure what I spent exactly – I did buy a little bit of gear (mixed use shoes, somewhere between trainers and hiking boots), but tried to generally be frugal when travelling (pretty much 100% hostels or less). Maybe around £3500 total.

There’s always questions about whether the Interrail ticket is worth it: it absolutely was for this trip. It came to 7.82 GBP per train or 0.0379 GBP/km, excluding seat reservations.

Part 1: Travelling to Isolation

I started as an 18-year-old leaving home. It’s the first proper time I’ve been alone, and certainly the first time I’ve been alone for such a long time. All I had with me was the clothes I was wearing, a 65-litre bag, and a second small backpack. The big bag contained clothes (unfortunately a wide range because of the wide climate differences I could be facing), a hammock and sleeping bag, a little camping hob and all the other small bits and pieces. I had a drone and a jacket in the small bag. When I do this trip again, I’ll probably still need this arrangement, but I’ll drop the camping hob as I didn’t end up using it (although I had planned to and gotten quick close at a couple of points).

I had done a short practise trip of 3 days in the Summer, over more familiar territory between London, UK and Rijeka, Croatia, via an overnight hammock atop a hill in Interlaken, Switzerland and an overnight train.

The first train I boarded was on the Elizabeth Line from my local station, out west of London. I originally had a plan to take a picture of the front of each train I boarded. That would’ve been nice, but was unfortunately quickly forgotten about – I did get a couple though.

If you’re also coming from the Elizabeth Line, switch onto the Thameslink at Farringdon and you can get to the international station, all included on Interrail. This was one of only 3 points in my entire trip that the planner app didn’t have accurate information – it doesn’t seem to have Thameslink services. If you’re a frequent lurker in the Interrail subreddit, you’ll often see advice not to rely on the Rail Planner app: maybe I got lucky, but most of the time, I only used that app, and everything was OK.

Not much to say about the Eurostar – it’s a great price with Interrail and too expensive without. Arrival into Amsterdam (my first stop) was a little late, as the train was diverted through The Hague, a place with a lot of bureaucracy. It’s also the location where the ICTY trials were held, a history which would frequently pop up in unexpected places across my trip.

I would rate Amsterdam an ‘OK’ in my arbitrary ranking system. It’s a nice city with some character, and of course good urban design, but it just didn’t feel like what I was looking for (not that I knew what I was looking for). Maybe it was biased by my feelings having just left home for quite possibly 2 months. Unfortunately, I don’t have many pictures of Amsterdam.

I spent my first evening sat on a park bench in the rain (which also didn’t help the ranking), in the dark, with the occasional jogger or walker, just getting used to the feeling of solo travelling.

The feeling of loneliness is real at the start, in the first few weeks. For me, it was worst in the evenings, but I remember it did feel like it was sort of always there, hanging over me. But it does get better. I guess it also helped I was travelling to more and more physically isolated places. I felt the loneliness less when I also felt physically isolated, if that makes sense. Part of my aim for this trip was, as I said, escaping my introversion at least a little, but also just experiencing true isolation, like nobody on the planet knows where you are when you are there, and you can blend in with the surroundings.

In most cases throughout my trip, I spent 1 whole day + a morning or afternoon in each city (after dropping off my backpack or checking whether I could leave it for a while after check-out). Some cities I spent 2 whole days in, but that was the exception as I knew I had a lot of ground to cover.

There’s always loads of questions on the Interrail subreddit about whether a trip is realistic regarding the timing, and the consensus is usually that 2 or 3 full days in each city is the minimum, otherwise there’ll be more travelling than seeing. This does seem a good guide for the average traveller, but adjust to what you know you’ll be interested in and adjust to what your aims are. I moved a lot quicker than most because I knew I was likely to have to cover a lot in a relatively short amount of time, and I had the occasional deadline along the way (some of which I met, some of which I didn’t). At the same time, don’t enforce it as if it’s a rule. Move at a natural pace: the Interrail pass gives that flexibility so you can decide what’s next the night before (at least off season, I almost never had a problem finding hostels). Also, if you can’t move how you wanted for reasons you can’t control, feel free to stay put. In the end, I was mostly happy with how long I spent in each city, apart from a few exceptions, and got better at judging how long I would need in them as I progressed. Another week or two for the same cities would’ve been perfect for me.

I walked a LOT on my whole day in Amsterdam, but honestly, I can’t really remember anything specific. After experiencing the isolation of the first night, I knew I needed to try harder the second night. Well out of my comfort zone.

Luckily, the hostel was quite a good one for socialising, and I managed to find 3 Turkish guys trying to setup a game of Monopoly in the social area. Obviously, it feels weird interrupting a group, but chances are most people are just as awkward as you and won’t say no :D. But seriously, just ask if you can join them. Don’t worry about being awkward. I should’ve taken my own advice more often. After going through the partially dismantled boxes of 3 board games, they quickly decided that there was nothing.

Luckily, I had bought a game of Uno with me, so, we just chatted for a while and played some Uno until 1am. A little exhausted from the sudden change in environment, it was time to get a little bit of well-needed sleep before waking up at 7am for my train in the morning. Thanks guys, and I’m sorry I can’t remember your names!

The next day, my journey was to Copenhagen via Osnabrück and Hamburg. I had about an hour and a half to spend in Hamburg, so I went to find something to eat before the 5-hour train to Copenhagen. Having heard mixed stuff about this service in terms of business, and wanting a seat, I had made a reservation (it was cheap anyway). I think in the end, that service is marked as ‘Please reserve’ by DB, but there’s no actual mandatory reservation in the database. Not sure what would happen if you didn’t have a reservation though.

I arrived in Copenhagen fairly late. I did cook for the first time that night – a meal well known to travellers, pasta bolognese sans meat (far too expensive and difficult to use the whole amount given I was moving quickly and couldn’t rely on a fridge), which would become a staple of my diet for two months. A guy who I started talking to the kitchen also let me have his leftover pasta (which of course, was the same). Then I went out and hung around another park for a while. The mini zip line thing in the children’s play area was fun. But it was very dark and didn’t feel totally safe, which was a nice taste of the freedom and responsibility.

Spent the next day exploring the city, the centre is a pretty good size to take it easy and explore on foot and take in all the main sights, the Kastellet fortress, The Little Mermaid statue. But also, just to see the centre, and chill in the parks. It’s a nice city. Looking for the first sunset of the trip, I went to the highest point in the city centre that I could find, The Round Tower – it wasn’t a bad sunset but also nothing special. Although a nice view over the city with the darkness gradually setting in and warm lights in mid-rise buildings gradually turning on (very different to the big capital city that I’m more used to), and there were two Serbian girls also up there.

I cooked again that night, wanting to compensate a little for eating out twice so far on the trip. If I had known I would be cooking again so quickly, I might have bought some meat the first night. I should’ve planned ahead a little better.

The next day, I wanted to keep moving, so I took the train for an hour over to Malmö. That route had the second mistake on the planner app, but luckily, I knew better in this case. It tries to force you to change at a random station (Hyllie) after the bridge – it’s not necessary.

- Tip: Usually, the best advice is to download the app for the country’s rail network. But 21 apps is a little too much. Usually, the app of each country can give you live and true times, which is useful sometimes, but particularly for claiming a refund – for example, none of the usual apps showed live/true data for Norway, except the NÅ app which I used as evidence for delay repay. If you’re trying to use minimal apps, DB Navigator and ÖBB Scotty are good places to start for non-Iberian and non-British Europe, even if you’re not going to Germany or Austria. They have good planning and DB can do live updates for a couple routes in other countries. SBB Mobile is also very good for live data for Switzerland, and sometimes Germany. But otherwise, those apps plus the Interrail Rail Planner app more than sufficed for me.

- Tip: If you’re going to be buying tickets/reservations/supplements, you can also buy a lot of countries’ (and often for a somehow cheaper price) tickets via the ÖBB site, which is easier to use with Interrail than the DB site. In fact, I usually defaulted to buying reservations where necessary from ÖBB (except in Poland, where I used the PKP Intercity site, and Sweden, where I used the SJ site). In my whole trip though, I didn’t need many reservations.

I spent a while chilling on a park bench in Malmö eating what I had bought from Lidl in Copenhagen, after taking a walk around the centre and the park around the Malmöhus Slott. It’s quite small a small centre and area, but a pretty good size to spend the morning before continuing onto Stockholm, on the 15:07 tilting train. Of course, I had to go to Lidl again before boarding the train to find something to eat on the 4-and-a-half-hour trip. Maybe it’s the tilting + sitting backwards, but this is the only time in the whole trip that I felt travel sick.

Originally, I had planned to go via Gothenburg from Malmö, then to Stockholm after, but engineering work made that impractical since Interrail wasn’t valid on the replacement busses (they weren’t quite standard replacement busses?) and full price was too expensive.

I arrived in Stockholm later that night. I would be in Stockholm for 2 full days plus a morning. I remember the feeling of loneliness creeping back in in Stockholm, particularly the second evening. I chose not a great hostel – kinda nice but also kinda out of the way slightly and not much atmosphere.

The next morning, I walked around the island, then took the ferry over to the next island, and visited the Vasa Museum (housing the world’s only preserved 17th century ship), which is well worth a visit (and free if you’re 18 or under), along with Skansen nearby. Skansen is a strange place: they call it an open-air museum which shows off the way of life of Swedes before the industrial era. They have an old village, consisting of mostly original buildings, transported to the museum piece-by-piece; a zoo – including arctic foxes (if you’re lucky enough to spot them), moose, lynx, brown bear, reindeer, and cats, alongside others; a ‘sea centre’; and an aquarium (run separately). I then found a nice burger bar to eat at (a little expensive, but also a very good burger), and then went to the old town (Gamla Stan) to walk around. I then crossed the water again to the south, and walked up the hill a little to get a view over the city.

The next day, I took walked around the centre and old town in daylight, found a very cute small statue of a boy watching the moon, then walked over to the town hall, then back to the metro station in the old town to take it out south a little to take a walk and fly my drone a bit in the nature reserve (Nackareservatet). The nature reserve was quite nice and peaceful to walk along the hiking path along the river.

After doing my first laundry of the trip the next day, I took the afternoon/evening train to Oslo. Stockholm was a really nice city and I had enjoyed my 2 days there, even if I had left a little alone at some points. So I was looking forward to seeing how Oslo compared. Anyway, that was a nice long (7 hours) ride with beautiful scenery and a beautiful sunset. The old trains are the best, and I really don’t mind the slower services. Better seats, more comfortable, and you can stand at the back and watch the tracks come out from beneath your train, which works quite well along this route because of the sweeping turns, straights, single track sections, and flashing signs warning of level crossings with their barriers coming up after your train went past.

When we eventually pulled into Oslo, over an hour delayed, I realised I no longer had my water bottle. I tried searching on the train, since I knew I had it with me when I boarded, but it probably had rolled to the other end of the train while I was staring out the back. And I didn’t mind the delay – even as we stopped over and over again to let freight trains overtake us (maybe we were delayed by enough that we became lower priority and not worth interrupting the freight traffic for). It’s part of the trip.

> Tip: don’t carry a reusable bottle, it’s just annoying. Instead, buy cheap plastic bottles and refill them. Take advantage of the deposit-return/pfant bottle recycling & exchange systems to get a new bottle fairly frequently and save some money. This way, you can have water and other flavoured drinks, and don’t need to keep track of a bottle. And you look like less of a tourist.

With the train arriving at 22:30, I didn’t have a lot of time to catch the last metro train that would enable to me to reach the hostel by 11pm. This was when check-in supposedly closed, but I think a hostel of this size does not care if you’re a little late and has 24-hour reception.

So, after a little bit of a sprint up the seemingly endless walkways from the platforms to the overbridge concourse at Oslo station (not using the travellators either because they were full of people standing still), and a race through the station, up into the street, and across and down into the metro station, I just managed to reach it in time and buy a ticket as I ran past the ‘ticket required’ line.

Oslo was a ‘NICE’ city – I don’t really go ‘into’ anything much (like museums) when I have only a day, I prefer to just walk around. One full day was plenty of time to walk into the centre from my hostel on the outskirts (where I was lucky enough to get a free upgrade to a private room because a big school group had booked all the bunks), have a wander, reach Kontraskjæret overlooking the sea, and then walk along to the architectural masterpiece of the opera house and the slightly less masterpiece look of the ‘Barcode Project’. Then back to the Kontraskjæret for a nice sunset. I think two days is probably the better number, to say you’ve properly seen the city, but I was glad I went a little out of the way to get here, even if it was just a day.

> Tip: try to use local train services where possible, make the most of your Interrail pass. For example, the night I arrived, I had to use the metro, but the next trips to and from the hostel, I could use the train.

Having successfully dodged any major works or unplanned delays until this point, it was of course time to get a little reminder that being a little spontaneous is required for travelling like this.

Because of track works, there was a replacement bus service for the first half of the way back to Stockholm. Having heard less than positive things about replacement busses in the UK, I was dreading this slightly – but in the end, it was no problem. Of course, not as good as travelling by train, but it was nice to see some different scenery and cross the border back into Sweden on the road where there’s an actual acknowledgement of the border. And it was comfortable enough.

At this point, I had been planning to have a couple of hours in Stockholm to eat and buy some food for the journey ahead, before taking the well-known sleeper up towards Narvik, as far as Kiruna. In Kiruna, I would spend a day and take a tour of the LKAB mines – the mines responsible for sinking the town to the extent that they had to physically move the not-deconstructed church across town (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-f59e6f5d-1dd0-4893-a52f-162b60a695d9).

I had already had to shuffle my trip a little, as about a week before I started the trip, LKAB informed me that my chosen day was no longer available due to low demand, and that I could move to the next day free of charge, or get a full refund. I had moved to the next day, which is why I had two days in Stockholm, which was nice, but did cause some shortage of time later as I had a later non-refundable accommodation booking.

So, when I got the email that the night train had been cancelled, I knew that the plan was yet again going to be messed up, and I no longer had a buffer day if I wanted to keep my reservations. The people at SJ were very helpful and worked with me when I used their online chat, so that’s great! More about that in a second.

Anyway, as I changed onto another tilting train in Kristinehamn, which had been waiting for our bus, we arrived in Stockholm a little late but with plenty of time for the later night train I would now catch. So, I went back to eat at the burger place I had found before – they were good burgers.

Around 20:30, I boarded the night train, and we set off on time.

My original night train 94 had been cancelled due to severe weather impacts in the north.

I had been rebooked with tickets for the number 92 night train to Luleå, which would take an alternative route.

It’s a bit difficult to piece it together. I believe that the coastal Bothnia Line, between Sundsvall and Umeå had been significantly flooded before I had even started my trip. This flooding persisted. There were also two freight train derailments, knocking out the Ådalsbanan, which is the preferred diversion route when the coastal line is shut, from what I understand, and another line which I can’t figure out 100% where. So, with capacity constraints, they cancelled some of the trains, including this night train.

Unfortunately, I cannot be sure exactly what route was taken. I know the train did not stop at Umeå C. I’m pretty sure that it did not stop at Sundsvall. My first image in the morning is on part of the Main Line Through Upper Norrland at Jörn.

There’s two options. If the Main Line Through Upper Norrland was still closed, we went via Östersund, onto the Inlandsbanan, then back down onto the Main Line Through Upper Norrland. Otherwise, we followed the followed the Main Line Through Upper Norrland between Bräcke and Vännäs, which is only used for freight normally, and usage as a diversion is rare as normally it would be possible to use one of the other connections (such as the Ådalsbanan) to avoid a short closed section of the coastal line.

For at least some length of time, option 1 on the Inlandsbanan was the only available option as the Main Line Through Upper Norrland was totally blocked by derailments. However, I think it might have just caught the reopening of a stretch the night before – so I think it may have been option 2 in the end.

Either way, it’s a shame I fell asleep – it would have been very interesting to see which route we took for sure and I’m sure the scenery would’ve been spectacular to witness on this rare route (either one!). Not one diversion, not 2, but 3!

In addition, I had been booked a hotel room for a night in Boden (one stop before Luleå), and my tickets on the Iron Ore Line stopping at Kiruna were replaced with through tickets on the day train the next morning – the very helpful people over at SJ understood my change of plans and were very nice. I would now miss my mine tour, which was a shame, but at least I was able to claim a refund, under the excuse that I was no longer able to attend the new date – they were very helpful as well, thanks guys and sorry I cancelled a little late. I did also lose my non-refundable accommodation in Kiruna, but I think it was only one night, and I got a free upgrade on the train and hotel room – so I’m not complaining.

My replacement tickets for the night train appeared to have been an upgrade (unless I misunderstood what reservation I had made initially), so thanks to SJ again, so I had a proper sleeper bed.

> Tip: the train from Copenhagen to Malmö, I think it was the Oresundstag, had lots of small plastic bags under the table which goes between the group of 4 seats (2 facing 2). As I found out, this is quite common and seems to be for collecting litter and then making it easy to clean up. But these ones were high quality enough that took a couple to use as plastic bags. It gets expensive buying them every time you shop!

The compartment was snug but nothing I wasn’t used to. I had previously taken the night train from Zürich to Zagreb on my practise trip, and it was about 12 hours. I chose a seat as I didn’t want to pay for a couchette. That was an experience – and honestly, a good one. Yes, I was tired the next morning and didn’t get much sleep, and travelled the longest distance out of the 6 of us in the compartment, but it was alright. I would recommend doing it at least once. It was a cool experience greeting everyone as they came in, from randomers who seemed to maybe be a little high but friendly, to a dad and his two daughters, to a guy from another compartment who got kicked out and replaced with another guy who seemed to be nice from the couple of smiles and laughs we exchanged. There’s no privacy at all, but that’s part of it. The very quiet whispers in a language you can’t understand, the occasional laughs shared as the conductor’s stare bores into the lady obliviously blocking the entire gangway with her and her bag in the middle of the might, and the compartment next door randomly blasting what sounded like a call to prayer at 6am in the morning before being promptly told to ‘turn off the music’ by the conductor.

But I was glad I would have a proper bed (or at least, as good as it can be) for this trip – I needed all the sleep I could get. And I slept well – I even managed to sleep through the other guy in the compartment who I had talked to for a while the evening before leaving the train.

We arrived in Boden later than scheduled, around 12:30, so a total of about 15 and half hours of travel. At this point, I was already beginning to be kind of happy that my plans had been forced to change. Now, I would see a little more of Sweden, visit the coast of the Gulf of Bothnia, and I would be able to travel the route to Narvik on a day train with a seat and proper window rather than awkwardly cramped into a couchette compartment.

Boden itself was very small and very much off the beaten track for tourists. But it had everything needed and was a nice break from the bigger cities, and a taste of what was to come. I decided to take the train out to Luleå that evening. It ended up being a bus replacement service again (this time a minibus instead of a coach, which didn’t even check my ticket), but never mind. Luleå was nice enough, not a lot there again, but I had a Max Hamburger burger (this town is their headquarters) and walked out to the inner bay, then across to the coast (or as close to the coast as is possible). Not a bad sunset either, and it looked pretty nice reflecting off the clouds and the flatness of the water.

I returned on the last train back of the day, headed back down the coast to Umeå, to Boden. I also had a talk with the ticket inspector, not for anything bad, he was just a friendly guy and happy to talk. If I had a penny for every time I had a friendly chat with a ticket inspector, I would eventually have two pennies, which isn’t much, but it’s interesting it happened twice…

The next morning, after taking opportunity of the hotel to do my laundry, I walked back to the station in time for the train to Narvik – I believe the most northern passenger-serving train station in the world outside of Russia.

I was lucky and got a seat right at the back of one of the carriages which was next to the window and was by itself (to make room for the doors). Much better than a cramped and awkward night train. It was also quite quiet on the train, not being the main tourist carrier.

The scenery along to Kiruna was nice, but nothing spectacular. The autumn trees painting the landscape with shades of green and orange was nice – although it’s a shame it wasn’t snowing, as that’s the best way to experience this route.

We paused for a few minutes in Kiruna at around 15:30, enough time to leave the train and get some pictures of it and the station (which is a new one built in the north of the town), and watch the powerful specially built LKAB trains haul their cargo.

As we pulled out of Kiruna, the scenery changed again. I couldn’t have asked for better weather at this time of year. The landscape was spectacular as we travelled along and above Tornetrask – the big water surface and huge snow-peaked mountains in every direction – then down into Narvik after you cross the border into Norway (there’s a brief flash of a flag sign as you enter the ‘protective tunnel’ after Riksgränsen).

Fun fact, the fully loaded iron ore trains heading down from the border into Narvik produce enough electricity to power the empty trains back up to the border.

As we pulled into Narvik, I was pleasantly surprised by the high-quality dual-language visual display. Here in Britain, we only really get dot-matrix – and Norway can afford it at a train station above the Arctic Circle, whilst we can barely afford it in London.

Most people had alighted at Abisko turiststation. So the remaining travellers were a mix of mostly locals and a few tourists – who, after I spoke to some of them, quickly realised were all hiring cars to continue their journey (mostly into the Lofoten islands) or were returning later. My original plan had been to keep moving to Tromsø by hitchhiking, as I had no accommodation here and wanted to reach there in time for the first night of my booked accommodation, to catch up to my planned route. I was still eager to keep to that plan, but after nobody on the train said they were going that way, and after I had bought some much needed food from the shop, I realised that it was better to stay put – I was exhausted after that 7+ hour sightseeing ride.

- Tip: always prepare food for a long train ride. Being hungry or lethargic really does make a long journey much worse. Try to have something substantial if you need it, like a pot pasta or pot noodle. If the train has a catering facility, they’re usually happy to provide hot water with a small fee. I got some free water because the card machine didn’t have an Internet connection both times they tried 😊.

- Tip: don’t push on if you’re tired – I knew this tip before I left for this trip, but almost forgot it. Staying put is usually the better decision.

Originally when I was making my plans early early on, I was going to try to stay the night in my hammock, in a sort of preparation for what was to come. I knew it was a long shot but there looked to be a nice beach just north-east of Narvik – unfortunately it was only served by public-accepting school busses on weekdays, so I would have to find somewhere else.

(I found out when researching how possible it would be to get to the Russian border at Kirkenes (yes, it’s actually possible to do on busses if you time things right) and then back into Finland at Utsjoki via Tana bru, without spending 23 hours at Utsjoki – many of the less trodden routes are school busses which carry non-school passengers. But of course, they only operate on school days, once in the morning and once in the afternoon.)

Narvik was an experience. A small town tucked away up North. Not really isolated, there’s loads of transport links – but it definitely felt like it. I was suddenly very aware of just how far north I was getting.

In Narvik, there lies one of those posts with lots of fingers pointing (not very accurately to other cities), stating that the North Pole lies only 2,407km away. Of the 22 cities shown, I would visit 13 of them on this trip, the furthest being “Beograd” at 3,660km away (in a straight line). I wasn’t sure why Belgrade was selected – it seemed like an odd choice, but maybe it can be explained by something I found out later. Also there is the Hiroshima stone, a stone from the zero-point field in Hiroshima, which the adjacent inscription “Never again Hiroshima. Never again Nagasaki.” Perhaps it was not the only reminder of World War 2 in the area, or indeed on the trip…

I stayed in a rather unique hostel, built into the basement of a church – not bad though, apart from sharing the room with 15 others.

Not wanting to give up on my hitchhiking idea, I did a little research on hitchmap.com and found that it might be possible to hitch out from a bus stop on the northern edge of the town. So, the next morning, I walked the 15 minutes there and set up. Conveniently, the bus to Tromsø does also stop here – I had about 3 and a half hours to try to hitch out before I would have to pay another 30 euros for a bus ticket (stupidly, I had prebought these bus tickets and they were non-refundable).

I didn’t want to end up at the intermediate junction at Nordkjosbotn (where the E6 and E8 join and run concurrently to Skibotn, or the road splits to Tromsø) since I didn’t want to end up stuck in that very small village. So it was quite an ask to get all the way to Tromsø in one go. In the end, most drivers pretended not to see me (an annoyingly large amount), but a couple smiled and shook their head or pointed (“not going there”), and two pulled over but then said they weren’t going there when they saw my sign a little closer.

From Narvik to Nordkapp proper, it’s a minimum of 4 busses over 4 days, one a day. Most people drive – many people don’t know it’s possible to do by bus, or just aren’t willing to spend 4 days doing it. Whilst I have a driving license, unfortunately I’m not old enough to hire a car yet – but it feels better reaching somewhere so isolated whilst not having the comfort of your own space.

The first bus pulled up the bus stop (which I was trying to hitchhike from) at around 1pm. It was quite an amazing bus ride with really beautiful scenery.

The bus pulled into the central bus station in Tromsø after a little under 4 and a half hours. I originally planned to have 2 nights here, but with the delays caused by the train cancellation, I now only had one night, so I was pretty determined not to waste time. I also hadn’t seen any Northern lights yet – rather annoyingly, one of the guys running the hostel showed me an amazing picture of the one right above the street outside the hostel the last night (the night I was supposed to arrive). So, after replenishing my pasta supply, I dropped my bags off at the hostel, cooked and ate quickly, then walked over the Tromsø Bridge.

On the east side of the city, there’s a rather overpriced cable car up to the mountain overlooking the city. The small building at the top was the finishing point of the first series of the celebrity-ish version of Race Across The World broadcast on the BBC a few years back. Unfortunately, it does not seem possible to get onto the roof of the cable car building anymore.

It began to drizzle a little as I reached the top – but it just adds to the atmosphere. Being out of either peak season, it wasn’t busy, so I only had to walk along the edge for a little while before I was out of range of most of the torchlights of everyone else. I stood overlooking the city for a little while, taking pictures, thinking about what I had already done and what lay ahead, watching the last daylight fade out of the sky over the horizon. I laid on the ground for a little while (I had a warm jacket, and the ground wasn’t soaked yet), looking at the clouds and the stars – no lights unfortunately, but I knew I still had plenty of time. I started making my way back around 22:30 – I took the 1203 steps down via the Sherpatrappa stairs to save on the cable car a little and to get another view out of the range of most visitors.

The next morning, I walked across the bridge again to visit the Arctic Cathedral. It’s a unique church, quite small on the inside but worth a visit (even if it is a little expensive).

I do regret not spending more time in Tromsø, although there was not particularly much to do after you’ve seen the centre if you don’t have access to a car and aren’t with a tour group.

But I had to leave fairly quickly. The next bus takes you well off the beaten tourist route – I think most people taking public transport stop here. The 150 route takes you off the main roads, as it serves isolated communities between Tromsø and the and Olderdalen on the E8. Interestingly, the bus takes two ferries, each about 25 minutes, which carry cars as well, but are synchronized with the bus timetable. The view from the ferries was spectacular.

The bus arrives in Alta around 6 and a half hours after leaving Tromsø at 4pm. It includes an additional stop at one or two service stations (as the bus doesn’t have an onboard toilet, and the bus synchronizes with connecting busses), which if I remember correctly, has free hot water.

Again, one of the only remaining people on the bus at Alta, I had just enough time to use the toilet in the nearby REMA 1000.

It’s here that it becomes clear why I took a hammock. There are no hostels in Alta, only a couple of overpriced chain hotels – and I did not want to break my streak by using one of those. Yes – I decided I would be OK hammocking well above the Arctic Circle. My equipment (sleeping mat and bag) was suitable to around -5°C, so I was well prepared. In the end it was about +4°C, so not too cold once wrapped up.

Initially, I tried wondering off into the bushes behind an industrial area – but quickly realised that there was nowhere suitable there and the hedges were too dense to push through, at least at night down the steep bank they were on. It was also at this point that the police minivan I had given a small wave to as I stood alone in the REMA 1000 car park looking at my map came up behind me and wanted a quick word.

Of course, it’s not illegal to wild camp in Norway and they have some of the best right to roam rules in the world. So nothing I was doing was illegal, except maybe a little minor bit of trespass, but they weren’t worried about that. They were more worried about what I was doing, clearly young and alone in this part of the world. Once I handed them my documents (interestingly, they wanted my British passport after I had already given them my Croatian one, which I was using to travel). They were also interested in where I lived, despite it saying on my passport (my normal answer of London wasn’t precise enough, and nobody knows Slough, so my next go to is Windsor, the home of the Queen, which was apparently quite funny). But after making a note that they had seen me, they offered me a little advice. Apparently, this area had some problems with drugs usage and needles, so it might be better to walk for around 20 minutes to somewhere else they pointed to on a map. It turns out this second location was a place I had scouted out in my research on street view. Basically, it was out the back of a car park next to the Alta Kultursal, a small university building, and a hospital and rehabilitation centre. So slightly dodgy, which is why I had looked for somewhere else.

Anyway, after around 15 minutes, they let me go and wished me good luck. Of course, I saw them again on my walk, and they offered a wave this time. I found my sleeping place, setup my hammock and slept.

The sleep wasn’t so good, but it was adequate.

The church in Alta, the Cathedral of The Northern Lights, is a rather unique design, built from concrete and titanium. As it is a tourist destination for seeing the lights, travelling north again becomes even more rare, especially by bus. It’s the first place I went in the morning, to wake up away from the car park that had filled up while I slept.

Alta is considered (by its Wikipedia page at least) the most northern city in the world, of course by some definition which suits it. Honningsvåg also claims this. From here, you could follow one road south 5,120km all the way through to Gela in Sicily: the E45 is the longest North-South E-road. Or, you can continue heading north, switching from the Svipper/Troms bus network to the Snelandia/Finnmark bus network.

Further north than Lapland, and extending further east than St Petersburg and Istanbul, this is the North-east extreme of Europe. It has a population density of 1.55/km2, less than Iceland and supposedly less than Siberia.

The bus 110 had left just before noon, carrying me, a couple locals, and a group of (I’m assuming) army conscripts around my age or a little younger, who would change bus to a place I would travel past later (I think?).

I can’t be sure, but I think this is possibly the most northern public bus route in the world. After traversing some unique landscapes, rising above the northern tree line where most plants become small grasses and the occasional shrub, it just pops above the 71st parallel north. The sole entrance to the island Honningsvåg lies on by land is by the 6,875m long Nordkapptunnelen. It carries, the E65 road, as well as the EuroVelo cycle routes 1, 7, and 11, and the European long distance hiking trail 1, down to 212 metres below sea level on a 9% maximum gradient. There’s another few tunnels through mountains, but when you finally emerge into the light of day on the other side, you’ve arrived.

There are not many other people on the bus at this point – I was one of 3 including the driver. Most tourists arrive by cruise, or by car, campervan, or motorbike. Very few arrive by bus. (Even fewer arrive by foot or bike, but we don’t talk about those.) Indeed, I saw and talked to nobody else who hadn’t come by one of those methods in the whole time I was there.

Honningsvåg can be considered the ‘base camp’ for Nordkapp. It’s tucked away on an island – which, yes, does mean that technically the most northern point of the main landmass of Europe is slightly further South-East, but you’re almost at the most northern point of the ‘main parts’ of Europe, and the most northern point accessible by road. It’s a strange feeling. There’s more isolated places on the planet for sure – but the isolation is doubled when you’re solo travelling up here. It’s not a ‘hidden gem’ – but those are rarely actually hidden and there’s no achievement getting to those places.

I have no source, but I think the REMA 1000 in the north part of Honningsvåg, known as Storbukt (where my accommodation was), is the most Northern supermarket in the world outside of Russia and Svalbard. So, as a little souvenir, I carried the plastic bag I bought there all the way home. The 71st parallel north passes right through it, only a few meters north of my accommodation.

- Tip: REMA 1000 is by far the most common supermarket in Norway, and it doesn’t have a bakery section, so if you’ve come from the land of Lidl bakeries, remember not to rely on it for a quick breakfast. I starved myself a fair few mornings.

The tourist centre at this time of year closes at 2pm, before the bus from Alta arrives, so I had to hope that my plans for the next day would work out. So, I walked along back to my accommodation from the centre where the bus finishes its route. After chilling for a little while, I walked back along to the centre as the night was falling.

And, at last, I had seen some northern lights. Hunting tour or private car not needed.

The next day, it was time to finally get to the tip. I put on the thermal layers I had bought, put on my waterproof jacket and trousers over everything, and packed as light as possible.

It’s unfortunately not possible to take any of busses which shuttle the cruise passengers to and from Nordkapp (I asked a couple), and the last local busses to Nordkapp were cancelled a few years back from what I , so the only remaining options (at least at this time of year) re by hitchhiking/car, or a single operator who operate a minibus from the tourist centre, stay at Nordkapp for an hour (which is probably enough, although it does feel like after all this time spent getting here, you should stick here more than an hour), then come back, once a day. At least on the day I was there, a minibus was more than sufficient, with only myself and 2 other people present on the bus – one of whom was a cruise ship passenger, and the other, I’m not sure.

At this time of year (actually starting the day I arrived), convoy preparations are made for the imminent arrival of snow on the last stretch of the E69 (the northernmost road in the world with connections to a major international road network) where it takes a left, leaving the Fv171 to serve Skarsvåg (the northernmost fishing village). When it begins snowing, all the cars and busses go in a convoy to and from Nordkapp a couple of times a day (once around midday, and once later at night). We didn’t have a convoy as the snow hadn’t arrived yet, but we did pass the truck putting out the neon-orange sticks that mark the edge of the paved road, in preparation for the snow.

15 days after I had left home, I had reached Nordkapp.

It is a pretty amazing place, and the sense of achievement is massive. Continuing my streak of luck, I had good weather – not amazing, but also with a good visibility distance. The visitor centre is of course mostly a tourist trap, but I quickly forgave myself for paying the overpriced entry fee – after all, it took a while to get here so you might as well make sure you’ve seen everything.

Unfortunately, there does not seem to be a marker for any of the EuroVelo routes, but there is a stone marking the start of the E1 hiking path nearby the famous globe. If you wait a little while, most of the other tourists from the cruise ship + bus combo will disappear to somewhere, and you might have the luck of getting some shots of the globe without anyone else in frame. However, this is not a normal tourist attraction – even when it’s busy, it’s still quiet. Both in terms of business but also sound. It still feels isolated if you turn your back on the visitor centre and stand at the railings, looking out at nothing.

This is not the true most Northern point of Europe, although it is a convenient location for tourists. But hopefully you’ve realised at this point, that just doing the tourist route isn’t enough. Technically, the most Northern point is Svalbard and Jan Mayen, further north, accessible only by flight.

Ignoring that for obvious reasons (I wouldn’t really call that Europe anymore, even if it technically is), stretching 1,450 metres further North, about 4km further West, and getting to sea level unlike Nordkapp, is the Knivskjelodden peninsula, accessible only on foot following a poorly marked path starting from the E69 south of Nordkapp. I feel comfortable saying that Knivskjelodden is the most Northern point in the world accessible only by public transport and a little walk. There are other places further north, but they are only accessible by flight.

However, walking the path, especially at this time of year, without access to a car parked at the small layby a risky idea. There is no means of transport back to Honningsvåg except hitchhiking, which is obviously unreliable, especially on cloudy nights without the Northern Lights since there will be fewer tourists driving this road to go hunting for them. It being one of these nights, I was more than a little worried about the prospect of a very long rainy night walk (~30km) back to Honningsvåg after the 18km hike, with no food or shelter.

But I was only going to be here once. So, after surprising the bus driver by asking them to drop me off at the layby on the way back, they kindly discounted the bus ticket a little and wished me good luck (of course after asking me if I was sure I knew what I was doing).

If I had felt isolated at Nordkapp, I hadn’t known what the word ‘isolated’ meant. Quickly, the small layby car park with two or three parked campervans went out of view – I still don’t know who they belonged to or why they were there.

I did not see anyone else as I traversed the path to the end of the world.

My only company was the worsening rain, the sound of the wind whistling across the barren hills, and my shoes (my only pair for the whole trip) sinking into the waterlogged mud. But it was a fitting atmosphere, and matched the rest of my trip perfectly – not too easy as it could be in summer, not too tough as it could be in the depths of winter. Weather miserable enough to feel like that’s how it should be.

The final section of the path leads across a slanted plane of slippery rocks, threatening to pull you all the way into the sharp rocks that mark the coast if you slip. And it is impossible not to slip at least once in the rain. Having slipped probably around 3 metres down and managing to stop my descent on a lucky small flat section of grass between two rock planes, I took my time tiptoeing the last section.

As you stand at the end of the world, looking into the vast nothingness, remember that there’s only maybe 25,000 people standing further North than you are stood – or a little more than the capacity of a small arena/stadium spread across more than 13.5 million square kilometres.

I did not feel much as I took a seat and watched the waves crash against the perilous rocks (a swim in the Arctic Ocean here would not be a good idea). Maybe a bit isolated, but not as much as I expected. Maybe a little out of breath, but not as much as I expected. Maybe a bit content. Maybe a bit fulfilled. Maybe a bit nostalgic. Maybe a bit relieved. Maybe a bit scared. But not as much as I expected.

I don’t want to spoil the feeling of isolation here for anybody that might end up here after reading this. But if you got here like this, then you got here. Not quickly. Not in something comforting and familiar, like your own car or campervan or motorbike. Not cheating by flying, an invention that has shrunk how we view our world. But at the mercy of everyone else, and by letting the world drive past you – although that’s not to say you were lazy, not by any means. This is as far as you can go North, travelling in this way. ~99.999696% of the world’s population is behind you right now.

It did not feel like a particularly special achievement at the time. That has come later, far away from the land of emptiness and remoteness and isolation, far below the tree line, far below the Arctic Circle, increasing as I rejoined society in cities further south, and increasing now that I’m writing this, from somewhere familiar.

A swim in the Arctic Ocean here would be a good idea – but I didn’t.

It was my birthday today. I turned 19 as I stood here, alone.

Part 2: Just Head South

I spent a little while there, thinking about things I can’t remember. Soon it became necessary to start heading back otherwise I would definitely lose my small chance of an easy way back to my accommodation, as the sun was already beginning to set – although it just looked like things became darker, the way things do when you can’t see the sun behind the clouds.

Turning around, heading back up the rocks to the path back to civilisation, there were in fact two other people there, a husband and a wife. I’m glad I didn’t realise they were there before I reached the end of the world. A quick “hi”, then I left them a little time to get a head start before I walked slightly slowly behind them, watching them climb up the hill away from the sea. I knew that they would be my opportunity back, but I also didn’t want to intrude, so a game of remaining behind enough to give them the feeling isolation and keeping myself out of sight, but also close enough so that I could catch up with them towards the end, began.

The rain had stopped for a little while at the end of the world, some sort of reverse pathetic fallacy. But it began again as I also ascended the hill, leaving the ocean behind me.

Sure enough, I timed it pretty well to end up joining them about 20 minutes from the car park, where their car was parked. They were more than happy to offer me a lift back to Honningsvåg, although they said they would continue that night to Lakselv – a small town which I would later pass through.

We did not reach the car park before we had to turn on our torches, but it did not matter.

After they dropped me off at the REMA 1000, I bought a few things to cook dinner – a basic pasta sauce of course.

- Tip: cooking is usually cheaper than eating out, and healthier (although make sure to get a balanced diet – I was eating more than just pasta). But remember, if you’re moving quickly and can’t keep cooked food cold or preserved, you can’t cook in batches. So often a full meal, especially with meats, might be more expensive in some cases than eating out.

After cooking dinner, I made my plans for the next day. I had originally planned to leave the next day, but I quickly realized that there was no particular rush once I realized my plans to head east to the most Northern point of the EU at Utsjoki Nuorgam, and Kirkenes, Russia, and the Finland/Norway/Russia tripoint (I believe the only place where 3 time zones meet at a single point) were unfortunately unrealistic as I had a deadline to meet my parents in Helsinki. So, I decided to give my shoes an opportunity to dry out properly, along with the rest of my clothes, and had a rest day. My first real rest day of the trip.

Lots of people have that feeling when they do nothing all day that it’s a wasted day. Sometimes I feel like this. Having a break and staying in your room (especially as I had a private room (with shared kitchen) at Honningsvåg) is fine to gather yourself. At this point, I had run out of plans, and now only had a rough idea of what was next. Prior to this, I had planned each train and each night’s accommodation. So, I would just travel in roughly the right direction to reach Serbia, and take it easy, at least for now.

Having not seen the Northern Lights at the most Northern point, and being sceptical that I would see them again, I did walk back into the centre again that evening to see some. And I’m glad I did.

I had to leave what felt like a mini holiday in itself the next morning. My bus would leave from a stop next to the accommodation, and I had about 50 minutes between the check-out time and the bus – not enough time to walk into the centre, but more than enough time to find something to eat at REMA 1000.

Leaving Honningsvåg was as much an experience as entering it for the first time. As you again go through the tunnels, whilst not that much physically changes, the feeling of isolation begins to wear off.

The bus was again the 110, but this time I would take it only as far as Olderfjord, the junction where the E69 leaves the E6. Here, the buses all meet up for a few minutes, then leave in their different directions. I switched onto the bus 140, to Karasjok.

I did not know exactly how I would get out of Karasjok the day after I arrived there – whether it was hitchhiking, or a non-state operated bus route into Finland.

As I arrived in Karasjok, I can only say the atmosphere was eerie. Again, I was one of two or three people getting off the bus, and as I walked through the town, it was spectacularly quiet and the E6 road was not that busy. I was heading for a small monument hidden away and unsigned, which I had seen on Google Maps and which had piqued my interest.

I’m not sure what exactly they were, maybe huskies or wolves, and I’m not exactly sure what triggered them, maybe me, but as I walked along the pavement of the silent road, an almighty howl began, like out of a movie. The quiet and valley landscape made it sound like the sound was coming from every direction. It sounded like the souls of the damned, perhaps the very ones buried here. The overcast weather, diffuse lighting, and emptiness all added to the creepiness. I decided at this point, I would not sleep in my hammock that night.

I found the monument eventually tucked away. The inscription in two languages – Norwegian and Yugoslavian: “In memory of the Yugoslav prisoners of war who lost their lives in Karasjok during the war 1940-1945 and who were buried here”. Even this far north, wars cannot be escaped.

Karasjok was the site of one of the first four Nazi concentration camps in northern Norway. In 1943, 374 political prisoners and prisoners of war, mostly Yugoslavs were landed at Narvik, and transported to Karasjok, tasked with expanding the 18km road to the border with Finland as Karigasniemi. This road would become locally known as the ‘blood road to Finland’. Other ‘blood roads’, also built under similar conditions were built by Yugoslavs and other prisoners in Norway.

From nrk.no:

The German chief engineer who was responsible for the construction of the road is said to have said the following in the opening speech of the camp when he arrived in Karasjok: “It’s 18 kilometers to Finland and for every 50 meters there should be one dead person.”

One of the reasons the SS could let so many of the workforce die was that they did not have the status of prisoners of war, but were sentenced to death in Yugoslavia for having been partisans. Some were also innocent civilians who were caught in retaliatory actions against villages that helped the partisans.

The Yugoslav prisoners had the worst conditions of all the concentration camps in Northern Norway – ethnic Serbs were treated the worst, but Bosniaks and Croats also suffered alongside them. After four or five months, the prisoners had reached the end of their stay. Only 111 of them were still alive. 45 were then shot in a massacre just before their transportation out by SS and Norwegian officers. The dead were buried in 3 mass graves in Karasjok – one right along the road they helped to build.

I left the memorial behind – at least for now. It would not be the last time on the trip I thought about it.

In my search for something to eat, I found a pizzeria across the river. The pizzeria was inside some sort of small shopping centre, seemingly abandoned, and run by 2 definitely not Norwegian guys. With the décor feeling very strangely American and them doing more than just pizza, I decided I didn’t trust the pizza and ordered a burger instead. It looked like they had just hosted some sort of pizza party, but true to the town’s form, they were all gone and all that remained was crumbs of pizza and untucked chairs. I remained the only one eating there, apart from one individual who came in, talked to the guy running the place, then left without ordering anything but a small drink. Thoroughly spooked by this point, I ate my burger as quickly as possible and left.

I paid for a small hut in a camping site just outside of town. The hut did smell slightly strange, but I decided that whatever the danger in here was better than whatever was going on outside.

Still alive the next morning, I went to buy the supplies for the 7-8 hour bus ride ahead from the local REMA 1000 – feeling more comfortable after finding the supermarket wasn’t also empty. It was of course, just a normal town.

The bus was my only real route out of here, unless I wanted a very early 4-5 hour walk along the blood road to the border to start my day, so I paid the 90 euros to take me to 450km to Rovaniemi in Finland. First via the blood road to the border at Karigasniemi, then along the E75.

- Tip: bottle recycling schemes are a great way to drink water and have non-water drinks without carrying a reusable bottle, or several bottles. But before you cross a border, exchange all the ones you have for fresh drinks – the bottles from one country can’t be recycled in another, and you’ll lose the deposit you paid on it.

The bus ride did take a long time, but it was not boring. It was a relatively quiet bus – of course – and the driver had put the local radio on, which was a nice change from my own music. There were a couple stops along the way to buy further supplies or have a walk. Along the way, we managed to see some reindeer in the road. And the scenery and landscapes rolling past were so different for me, that it was always interesting. This stretch of the trip also included the most eastern point on my trip, close to Inari.

On arrival in Rovaniemi, I checked into the hostel – which was quite small and a very relaxed affair – then went to find a pizza and walk around.

It was very early for the tourist season, so the place felt pretty relaxed. Rovaniemi suffers greatly from overtourism in the winter peak season.

I had only a long morning to spend in Rovaniemi, but I quickly realised that unless you’re on an organised tour or have access to a car, there’s limited things to do, especially out of season. So, against my better judgement, I took the bus to the Santa Claus Village.

The village was mostly closed and mostly empty – a strange way to experience it. There were a few reindeer in holding paddocks, and the very occasional tourist taking the very overpriced reindeer sleigh ride (400m for some insane amount of money) – where both the reindeer handler and the reindeer looked equally as glum.

Thoroughly disappointed (although I fully expected that) with the village, I took the public bus back towards the city but via a longer route, which allowed me to hop off and walk across the Kemijoki river and up the hill on the east side of the city to get some drone shots just out of the restriction area of the airport.

I got back down in time to catch the 15:35 train to Tampere. The train journey was nice, but unfortunately it was dark for most of it, and it arrived quite late, at around 10pm.

Tampere was a pretty great city. I don’t think there’s anything particularly special that I found on my one day there, but it’s just got a nice layout, isn’t too small, and isn’t too large.

The view from the hill just West of the train station is decent, and the city is nice and walkable. There’s a nice mix of old and new, and I didn’t see any blight. I saw lots of squirrels and birds. It’s the second city of Finland so that has advantages, but it’s also not far from Helsinki.

After walking around for the day, without a backpack – so I did end up carrying my pasta sauce in my pockets and the mince meat (which I had decided to treat myself to) in my hands for about an hour as I wandered the city (probably looked a little strange thinking about it :D) – I cooked a bolognese actually with meat, as well as a little pre-grated cheese, for myself, as a sort of congratulations for surviving so far. If you find yourself in Finland, I’ll recommend his city, maybe just for one full day.

My next destination was Helsinki (only a short train ride away), where I would stay for one night in a hostel, then meet my parents the next day, travelling to Tallinn together.

Helsinki was just OK. The southern part is more walkable, but there is quite a lot of traffic nearby the centre (like surrounding the train station), and it just didn’t have quite as nice a vibe as Tampere. Glad I didn’t skip it since there were some nice parts, but I definitely didn’t need any more time there than the day I spent there.

On my first night, I just took a walk down the south tip – there’s a nice park stretching along the coastline – then back up to the beach at Hietaranta.

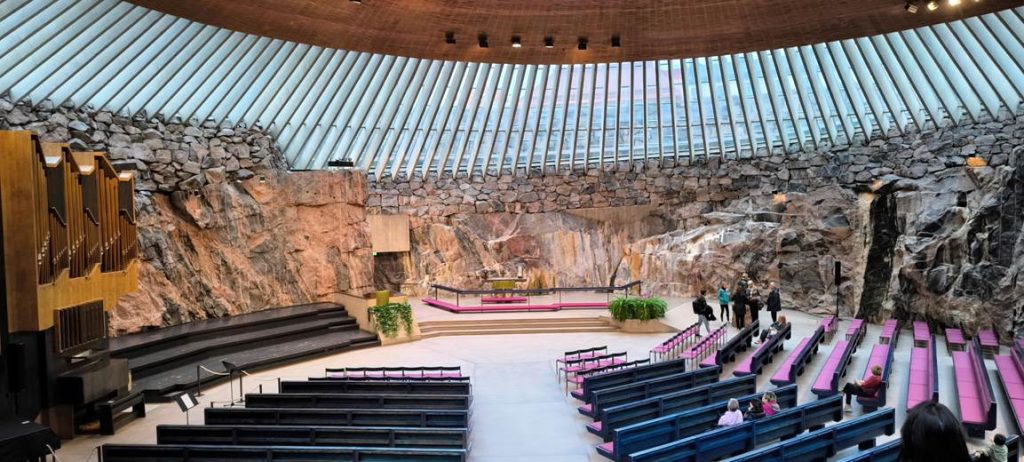

I met my parents the next morning, and we went to an interesting church, before catching the ferry over to Tallinn. The journey took about 2 hours, but it felt longer – I guess there’s no scenery to watch to pass the time.

We arrived in a rainy Tallinn, but despite the rain, it still felt like it was quite a nice city just from the brief walk through. We spent the following day exploring the city. Like many European cities, the centre is clearly old and well preserved, converted for modern purposes. It was also the first Eastern Orthodox country I would pass through on my trip, which meant more churches but slightly different now.

I had originally planned to stay in Tallinn only one day, and then continue south. However, I decided to join my parents for another day. We hired a car and drove out west of the city. Possible by train, slightly annoyingly, but not in the time we had available before they had to return the car to the airport for their flight home.

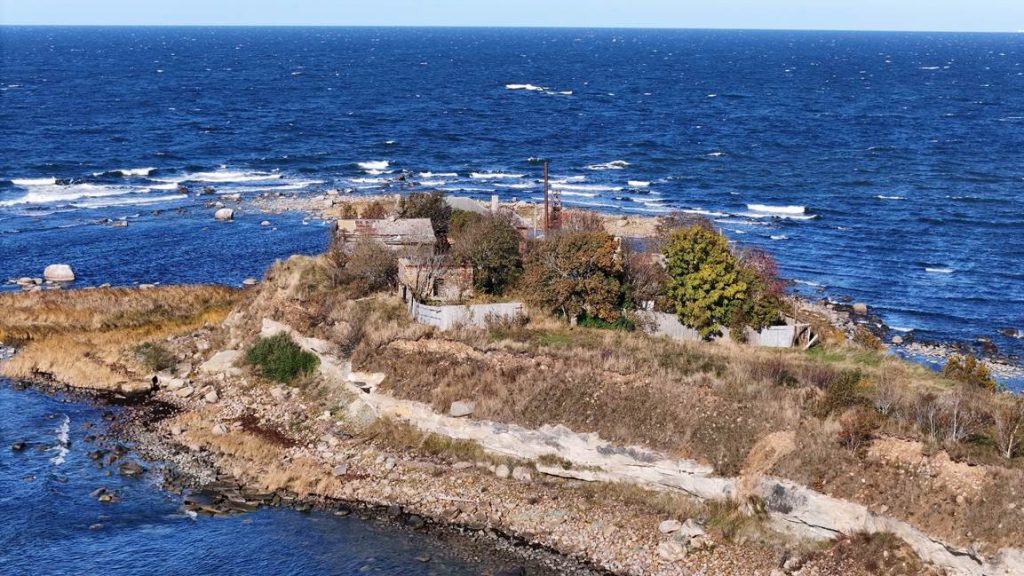

We stopped off first on the northern coastline at some sort of abandoned building. Interestingly, there seemed to be potentially a school trip down to the coast right next it, but I’m assuming the building was off grounds to them.

We drove on a little again, and stopped at the nice waterfall at Keila-Jou.

We walked there around there for a little while, then carried on to Paldiski. We didn’t spend long in Paldiski – it feels like a remnant of the old world with absolutely no one around and a long stretch of unmarked tarmac road stretching along the coast northwards, adjacent to the wall of the shipping/ferry terminal. And the lighthouse at the end, which was the true target, was closed.

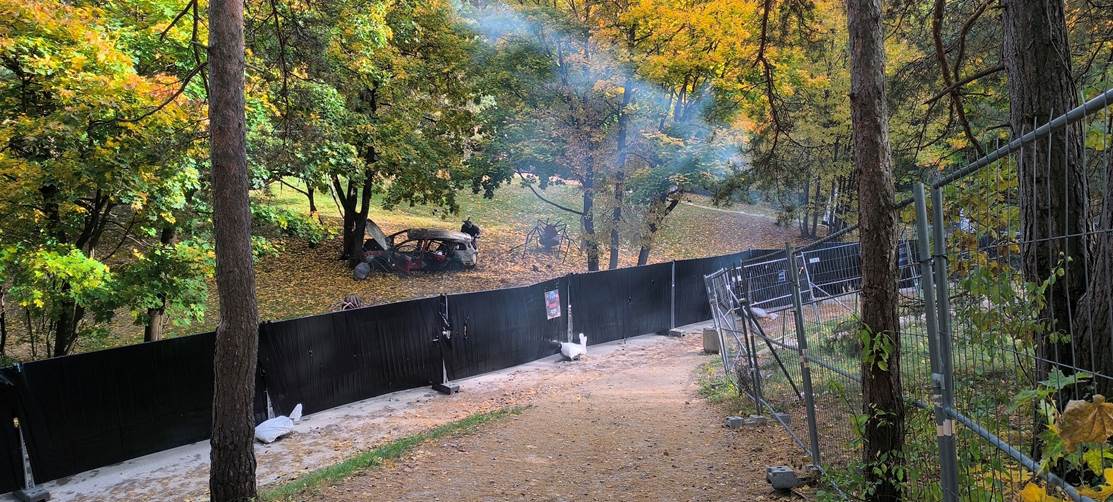

Having time left over since there was nothing at Paldiski, we drove on to Rummu. Rummu is strange place, an old, abandoned quarry with an artificial lake now filling the hole, and the spoil from the quarry dumped on one end creating a weird artificial hill (water erosion creating a unique appearance over the years) overlooking the lake and the decrepit buildings which have been flooded with water. Apparently, the place is quite popular in the summer, and there’s some leftover makeshift deckchairs and pontoons with small buildings, looking like they’re used as shops in the high season. It makes for a nice view from the hill. If you’re travelling through, I would say it’s well worth the 1h 15min bus journey from Tallinn (each way).

Perhaps at this point you might feel like you’ve somehow seen this before…

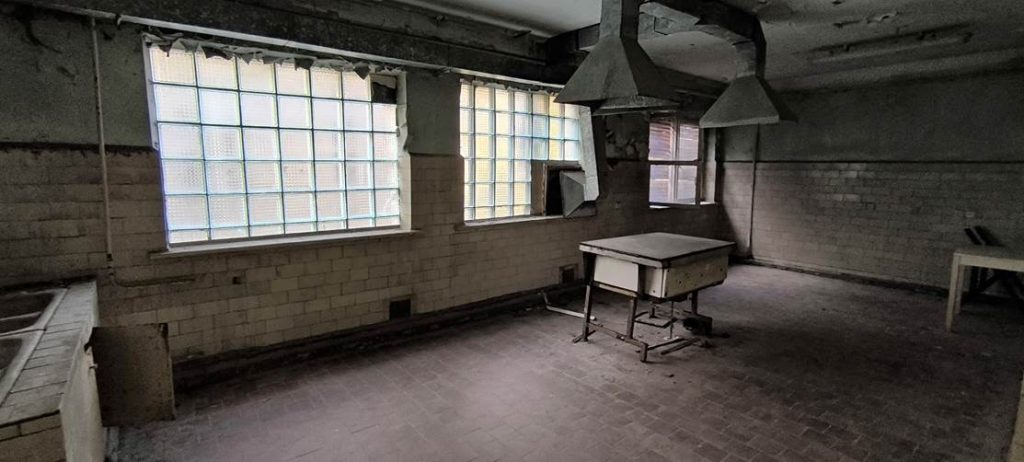

Adjacent to the quarry, and included in its entrance fee in the off season is an abandoned prison, open to the public without tour guide, and with – let’s just say, at least when we were there – a very relaxed attitude to security.

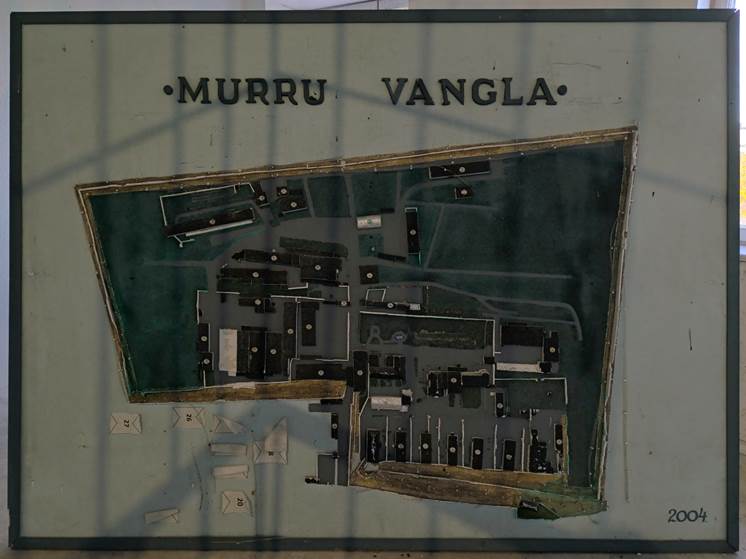

The prison was opened as Murru Prison in 1938. In 1961, part of the prison was separated and renamed Rummu Prison, which existed separately until 2000. In 2011, Harku Prison merged with the prison, preparing for their closure in 2016, when all prisoners were transferred to other prisons nearby.

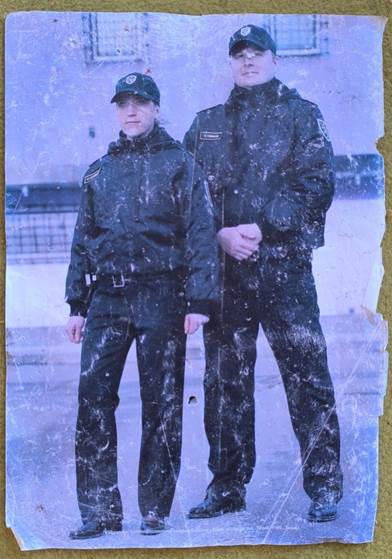

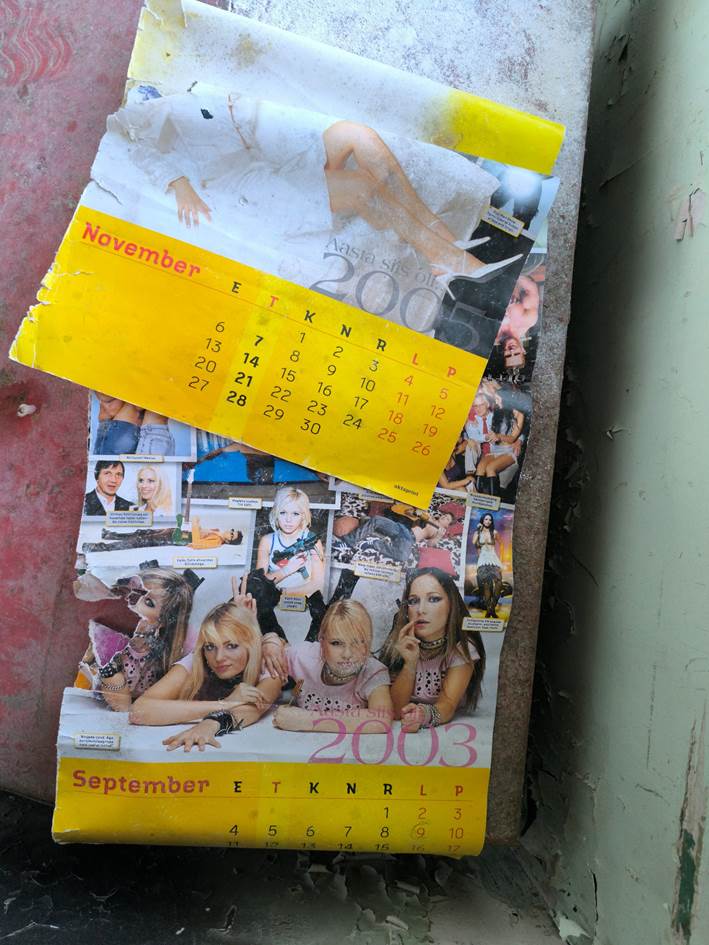

It’s a very interesting place to explore. Despite not being abandoned for that long, it had obviously fallen into disrepair whilst the prisoners were still incarcerated there. I had been wanting to do some urban exploration for a while, so this seemed like a good place to start – properly abandoned and with original leftovers untouched and unmoved, almost totally free movement, but with some feeling that it wasn’t totally unsafe, despite the crumbling staircases and dangling (I’m assuming isolated) cables. A very small part of the prison is a museum, but even there, there was no staff. The rest of the prison was almost totally empty – we saw one worker standing outside, and one other couple exploring the prison. It was easy to access areas that apparently weren’t supposed to be accessible, as the signs had gone missing from entrances – so when you walked to the other end of the corridor and turned around, only on that end was a ‘no access’ sign, also mostly torn off the wall.

It was after we left the prison – heading back to the airport where we would drop off the car and I would wave goodbye to my parents as they headed back home – that I found out that the music video for “Faded” by Alan Walker was filmed in Paldiski and the Rummu quarry and prison. After watching the video, I could recognise places we had been (such as the long empty road in Paldiski), and wished I had looked it up before so that I could’ve attempted to recreate some of the shots of one of the most viewed and liked videos ever uploaded to YouTube.

After saying goodbye to my parents at the airport departures, I made my way back into the city. Not wanting to cook with the substandard kitchen in the hostel I had bought a room in for the night, I made the bad decision to just go to McDonald’s. Being a McDonald’s employee in the UK, I’m used to apologising to customers for long waits. But 54 minutes was unexpected.

I had an early 10:10 train the next day. From here, the trains would now slowly funnel me back into the main European railway network in Poland via the Suwałki Gap. Luckily for me, the train service in the Baltics had recently improved – indeed it was almost perfectly timed for my travel purposes, although one train a day through Tallinn – Riga – Vilnius, then one a day Vilnius – Warsaw – Krakow still isn’t particularly a lot.

In Estonia, the trains are operated and owned by the national operator. Then there’s a guaranteed cross platform transfer at the border with Latvia (Valga). From this point, the train is owned by LTG Link of Lithuania, but operated by Vivi of Latvia whilst in Latvia (with no other changes necessary). Then there’s one more guaranteed connection at Mockava where PKP takes over on standard gauge into Poland. Easy.

If you want to spend a day in Riga, that means about 24 hours and 15 minutes – you just catch the same train the next day. Then, you’re basically forced to spend a night in Vilnius, so you might as well spend a whole day or two, and a morning, there as well since it’s a nice city.

Although, as I’m writing this, it looks like the service will improve from Vilnius into Poland from… today! That’s the 14th of December. One hour less travel time from Vilnius to Warsaw, and two hours less from Vilnius to Krakow, plus dynamic pricing and new trains. So safe to say, things are looking up for the Baltic rail network (and of course, at some point, Rail Baltica might arrive).

Back to the actual trip, I left Tallinn in the morning, and arrived 6 and a half hours later in Riga.

Riga was unfortunately a little disappointing. The old town centre is quite nice, but quite small and it’s unfortunately not helped by traffic surrounding the centre, turning a relatively nice riverside walk into something quite loud. Still a nice city worth visiting, but unfortunately the worst out of the Baltic capitals in my opinion. But it’s got some nice buildings, and I met some people in the hostel.

On the morning of the next day, I explored a little more of the city, going up the tower of the St. Peter’s Church. I then walked along the canal and around the parks just to the north-east of the old town, and ran into some sort of filming.

Next stop: Vilnius. I was tempted to go via Daugavpils, but my understanding is that trains don’t run from there to Vilnius.

Vilnius was a nice city. After a walk through the quaint ‘independent’ Užupis ‘republic’, I walked up a hill in the middle of the city to see some sort of film set with smoking cars and giant spiders to the Three Crosses Monument. As I walked up Gediminas’ Hill, there was a massive downpour for about 10 minutes, making sure I wouldn’t have a dry bench to sit on for the rest of the day.

Vilnius is one of the only cities I regret not spending another day in. With another day, you could visit the picturesque Trakai Castle apparently easily accessible, or spend time exploring the eastern part of the city.

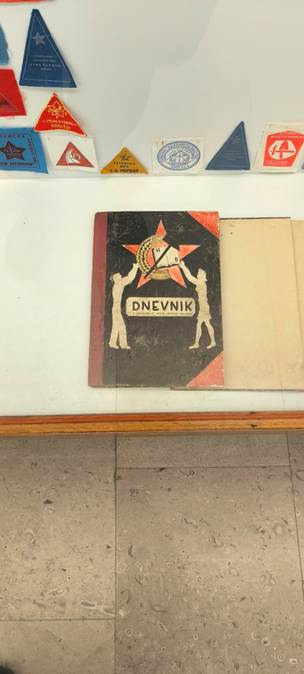

However, at this point, I had decided on a very rough route through Europe, carrying me south to Montenegro. To access Montenegro by train, the route is from Belgrade via a relatively famous route. More about the route when we eventually get there. However, at this point, I knew of impending trouble in Serbia. On the 1st of November 2024, the train station canopy outside Novi Sad train station had collapsed, crushing 16 people and injuring another. Quickly, it was realised that this had occurred due to negligence by the Serbian government and China, who were very involved with the recent renovations. China has a huge influence in Serbia, and are currently constructing their high-speed rail line from Budapest to Belgrade. This line has been pushed back and pushed back and pushed back again.

Since then, there had been regular huge protests across Serbia, mostly organized by student groups, who’s aim is to remove Vučić, the Serbian president, from power (as he is seen to be ultimately responsible for the negligence, among other things). The most major of these involved 400,000 people protesting in Novi Sad. The Serbian government shut the rail and road networks citing a made-up bomb threat. This was ultimately a failed attempt to reduce the number of people travelling to and from Novi Sad and Belgrade – people marched on foot across the country instead.

The 1st of November 2025 would mark the one-year anniversary of the collapse. There was a big gathering (strictly in remembrance, not to protest) planned for Novi Sad. I knew there was an almost 100% chance that the Serbian transport networks would again shut down for the days leading up to and after the events. So, I wanted to not be in Serbia from the 31st of October to the 4th of November if possible. We shall see together how that turned out.

What this meant is making quick progress through Europe to exit Serbia before the 31st, as if I entered after the 4th, I would not have enough time to complete what I thought could be the remainder of the trip. Therefore, I chose not to stay any longer in Vilnius, as it was already the 14th as I left. Whether this was the correct decision, I don’t know. Maybe in the end I would’ve just missed the exit day anyway if everything went to plan. Luckily, it’s not as hard to revisit in future as Nordkapp.

So, after a nice stay in Vilnius (and handily back in the land of the Lidl bakery), I set off for Warsaw. It was a long train ride, 8h 30mins. At least there was a decent sunset where the train stopped for a while at Białystok.

As we drew into Warsaw, I heard the guy behind me ask someone else on the train something, which I can’t remember anymore. However, it was obvious that he was also solo travelling, so we walked towards our hostels from the train station together. He was from Helsinki as it turns out, a little younger than me, and also solo travelling for the first time. I think he was using the bus through the Baltics, as he wanted to preserve his 4 days of Interrail travel for more expensive trips, which is a good idea.

The next day we walked around the centre a little, along the river then into the centre, before going our separate ways.

In the centre there was also filming going on for some TV show, involving horses. The pavement and road were covered with sand and there were some quite complicated barriers everywhere.

Warsaw was a little large for being easy to get around on foot, but it was a nice ‘big’ city. The big palace in the middle of everything looks nice and makes for a good (although expensive) viewpoint. Unfortunately, the city is quite busy with cars apart from the small old town, which is a little way from the modern centre and train station.

I walked to the Royal Baths Park then back again, before proceeding to get lost in the central shopping centre looking for a supermarket. As much as I would like to say that didn’t happen before or again, it did. A lot of them could use better wayfinding.

Then before my train left in the morning, I walked around the old city, then took up residence on a wooden hammock in a park near the station. The Żabka shops/cafes dotted everywhere serve very good and well-priced hot dogs – a very nice and enjoyable breakfast that I took advantage of throughout Poland.

The online reviews are mostly accurate it seems – Warsaw is nice enough but is certainly built as the capital of a country, its economic centre. Not necessarily its tourist centre. I guess very few cities around the world manage to be both.

My next train would finish the run of long distances and relatively high speeds, and take me to Kraków. A city which I would get more comfortable with than I expected.

I spent my first morning doing laundry, in a self-service laundromat/café. As I was eating my pancakes, and I still can’t figure out why, a woman in her maybe 60s or young 70s walked over to me and forced a 20-złoty note into my hand. I attempted to kindly refuse, first in limited English (which of course I didn’t expect to work), but having no effect other than her forcing it into my hand even more and talking to me about something I wish I could understand in Polish. Then I tried two words of poor Croatian which I (somehow correctly) guessed might be similar or at least understandable in Polish – “no understand”/“nie rozumiem”/“ne razumijem”, causing her to respond, of course with (in Polish), “you do understand, you do understand”. I gave up eventually and thanked her profusely. I still don’t know why she took pity on me, I was simply having some food whilst waiting for my clothes to be washed, but I guess I just looked slightly out of place (a feeling which you’ll get used to if you solo travel).

I spent the rest of the day exploring the old city, and eventually deciding to get the bus to Kopiec Kościuszki, which offers a fairly nice (and of course, pricey) view of the city – when it’s not foggy. Then I wandered through the dusk to the interesting and scenic Zakrzówek Park, before shopping for dinner at the Kaufland then taking the tram back into the city.

As I cooked that night, I decided I would spend another day in Krakow and pay a visit to Auschwitz.

Having talked to some people at the hostel, I realised that this might be difficult, as online tickets sell out a long time before (not helped by unofficial tour operators purchasing non-tour tickets, then lumping their group onto an Auschwitz provided guide), and on-site tickets sell out very quickly. My backup plan was the Wieliczka Salt Mines – a much more touristy affair that I wasn’t really massively looking forward to after the review by a certain trainhopper, but had a small fantasy of escaping the group into the depths of the mines (as demonstrated by that same certain trainhopper).

- Tip: Avoid tour groups like this, especially unofficial ones. For example, Auschwitz on-site tickets are actually free, if you can get them.

So, the next morning, I headed over to the train station to take the train to Oświęcim. I arrived at the station a little too early, so I walked around for a little while trying to find a waiting area with free seats. After following the signs which appeared to be non-sensical for far too long, I decided to walk down some stairs whilst looking at my phone to remind myself of the train time and see if there was a platform allocation yet.

- Tip: You know those things your parents told you not to do but you always did without a problem? Don’t drink from the cold tap in the bathroom. Don’t run with scissors. Don’t attempt to walk down steps whilst on your phone. Well, that last one suddenly makes sense.

In my defence, the stair edge colour wasn’t very well contrasted against the stair colour itself.

I missed the last step, and fell quite badly on my ankles, twisting the left one quite significantly into a position that it was not really made to be in, moving the whole left foot so my sole faced my other leg while the left leg stayed mostly straight and did not bend to accommodate the twist.